Perspective of Dr Knough*: Why do some people get lost so easily?

- Knowell Knough

- Nov 26, 2025

- 4 min read

Some minds simply navigate the world differently, and that difference can make a person feel lost more often than others. Let’s go on a small tour of why this happens—psychologically, cognitively, and emotionally.

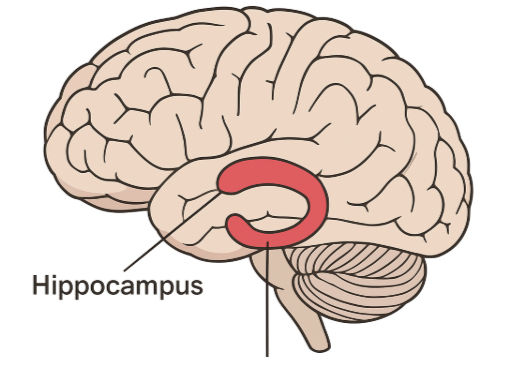

The brain’s internal GPS varies from person to person

Deep in the brain sits the hippocampus, a structure that builds mental maps, and the entorhinal cortex, where “grid cells” fire in geometric patterns to help us understand where we are in space. For some people, these systems are naturally less efficient, a bit like having a map that fades around the edges. Nothing is wrong or broken—just tuned differently.

Some traits that contribute to this situation are:

Weaker spatial memory (harder to remember landmarks or the layout of a place)

Lower sense of spatial orientation (north, south, left, right feel fuzzy rather than fixed)

Differences in attention (harder to encode the environment when focused on internal thoughts or conversations)

The “narrator” of the journey may be quiet

Some people don’t automatically narrate their movement through space—“I turned left at the bakery, now I’m heading downhill. ”Without that inner commentary, the memory of the route doesn’t “stick,” so retracing steps becomes tricky. Others do this effortlessly without ever realizing it.

3. Landmarks mean different things to different people

Some people intuitively notice stable landmarks—church spires, mountain silhouettes, specific buildings—while others notice things that don’t help them reorient, like passing cars, textures, or shop signs that change often.

If your brain stores the wrong details, the mental map becomes slippery.

4. Anxiety and self-doubt amplify the problem

A person who has gotten lost many times often develops an anxious loop:

“I’m bad at directions. I’m going to mess this up again.”

Anxiety hijacks attention, making it even harder to encode surroundings. It also narrows perception, so the environment appears less rich and more confusing.

5. The world moves fast; not everyone’s brain updates as quickly

Some people experience a slight delay in updating spatial information—so by the time they’re trying to orient, their brain is already one or two steps behind.

6. Not a flaw—just a different cognitive profile

Being directionally challenged is not a sign of low intelligence or poor effort. It's often linked with:

ADHD

Dyslexia

Highly imaginative or internally focused thinking styles

Anxiety or high neuroticism

Strong verbal intelligence (with weaker visuospatial skills)

But it can also occur all on its own, in perfectly capable and insightful people.

If you’re asking because you feel this way…

You’re not alone. There are many people like you who get lost easily. Often these people, far from being intellectually challenged, have:

A rich inner world

A strong verbal or creative mind

A habit of focusing on thoughts more than the physical environment.

Your brain simply prioritizes things in a way that is different from the orientation systems.

The good thing is, there are ways to work with it rather than fight it.

Use these strategies five strategies to improve your sense of direction:

1. Learn to Notice “Anchor Points”

These are fixed, memorable features that don’t change. They include:

Large landmarks: tall buildings, towers, hills

Distinctive objects: murals, statues, unique storefronts

Natural features: rivers, coastline, mountain range

Practice: On your next walk, challenge yourself to identify three anchor points and describe them in a sentence.

2. Use Cardinal Directions in Daily Life

Most people rely only on left and right, which rotate based on your body position. Start learning North, South, East, West as fixed reference points.

How to train:

In the morning, step outside and identify where the sun rises (east).

When indoors, try guessing the direction, then check using your phone’s compass.

With much practice, over time, identifying N/S/E/W should feel natural.

3. Mentally “Map” Your Route as You Move

Don’t just follow the path—construct it in your mind.

Ask yourself:

If I had to draw this on a map, what shape would it be?

Am I generally moving north, south, east, or west?

Where is the starting point compared to where I am now?

This forms a cognitive map, a key part of strong navigation skills.

4. Name Landmarks Out Loud (or in your head)

This helps lock in memory. Say, for example:

“The bakery with the blue awning is on my right.”

“The tall palm tree marks the turn.”

“I pass the river before reaching the bus stop.”

You’ll find that you remember verbalized information more easily.

5. Break Long Routes into Small Sections

Instead of memorizing a complicated complete journey, divide it into digestible pieces:

Home → Gas Station

Gas Station → Library

Library → Church

This is how professional navigators handle long routes.

By practicing these five strategies consistently, you’ll begin to build a stronger, more reliable sense of direction. Each technique — whether noticing anchor points, using cardinal directions, creating mental maps, naming landmarks, or breaking routes into smaller segments — trains your brain to pay closer attention to your surroundings. Over time, these habits work together to make navigation feel more natural and less stressful. With patience and regular practice, you’ll soon find yourself moving with greater confidence, clarity, and awareness wherever you go.

Dr Knowell Knough (clearly a pseudonym) is a psychologist who will periodically give his perspective on directional challenge and related topics.

.png)

Comments